Interpretazione di una placchetta in bronzo raffigurante un uomo nudo incatenato su pira ardente

di Attilio Troncavini

English vesion below

Desidero occuparmi in questa sede di una placchetta in bronzo tanto rara quanto insolita.

Nel suo celebre Les bronzes de la Renaissance. Les plaquettes, catalogue raisonné, pubblicato a Parigi nel 1886, Emile Molinier la classifica come opera di anonimo dell’Italia settentrionale della fine del XV secolo e ne segnala la presenza nel Museo di Berlino.

Lo descrive come segue: “752. Un Homme sur un bucher. Nu, de face, et le genou gauche appuyé sur la terre, la tete tournée vers la gauche, il est enchainé par les poignets et les chevilles sur un bucher enfiammé. A droite, una benderole plusieurs fois replièe sur laquelle on lit: I.T.F.” (752. Un uomo su una pira. Nudo, di fronte, il ginocchio sinistro appoggiato a terra, la testa girata verso sinistra, egli è incatenato per i polsi e le caviglie su una pira ardente. A destra, un cartiglio piegato più volte sul quale si legge I.T.F.).

Mostriamo qui di seguito un’immagine di repertorio che potrebbe raffigurare proprio l’esemplare conservato a Berlino [Figura 1].

Figura 1. Uomo nudo incatenato su pira ardente, bronzo, diametro cm. 3,2 circa, Italia settentrionale, fine del XV secolo, Musei di Berlino (?) (fonte Alamy).

Un altro esemplare è segnalato a Milano nei depositi delle Collezioni d’Arte del Castello Sforzesco (nota 1).

La relativa scheda del Sistema Informativo Regionale dei Beni Culturali (SIRBeC) è intitolata Caduta di Fetonte e così identifica al suo interno il soggetto, ma nella descrizione fa riferimento, seppur dubitativamente, a Prometeo.

Il collegamento a Fetonte appare del tutto ingiustificato (nota 2), ma anche quello a Prometeo non è pertinente. Egli ruba il fuoco agli Dei per donarlo agli uomini e per questo Zeus lo incatena a una rupe, ma nella sua iconografia compare sempre un’aquila incaricata di squarciargli il petto e dilaniargli il fegato.

Alcune importanti notizie sulla placchetta in esame le ricaviamo dalla didascalia del catalogo di un’asta tenutasi presso Spink a Londra in data 24 gennaio 2008 in cui è stato presentato un esemplare in bronzo del diametro di cm. 3,2 (lotto 52), come scuola italiana del XV secolo e con il titolo Allegorical figure of a Captive (Figura allegorica di uno schiavo).

Nella stessa didascalia, la scritta sul cartiglio viene riportata come I.T.F. oppure *T.F perché, evidentemente, la prima lettera non è del tutto distinguibile.

Si legge anche che, nel catalogo del Museo di Berlino, la placchetta era attribuita al Moderno e che fosse l’unico esempio pubblicato, che le lettere potrebbero essere la firma dell’artefice e che una placchetta simile forma il pomolo di una spada che si trova a Monaco di Baviera nella Collezione numismatica statale.

A quest’ultimo proposito viene citata la seguente pubblicazione: Georg Habich, Schwertknaufe der Renaissance, in Cicerone 1910 (nota 3), che ci ha consentito di rintracciare l’immagine del pomolo di spada [Figura 2].

Figura 2. Pomolo di spada, Monaco di Baviera, Staatiche Munzsammlung (Der Cicerone 1910, tavola fuori testo).

Per quanto riguarda la bibliografia di riferimento, la didascalia del catalogo Spink riporta Molinier n. 752 (vedi sopra) e Bange n. 440 (nota 4).

Non convince l’ipotesi che dietro la sigla I.T.F. si nasconda l’autore della placchetta per cui appare almeno prematuro pensare all’esistenza di un Maestro ITF (nota 5).

Per quanto riguarda l’attribuzione al Moderno, possiamo solo citare, senza sottoscrivere alcuna conclusione, la placchetta raffigurante una Deposizione, di cui si conoscono numerosissimi esemplari in altrettante varianti, il cui la disposizione delle braccia e delle gambe del Cristo può ricordare quella del nostro uomo [Figura 3, nota 6].

Figura 3. Moderno, Deposizione, bronzo, collezione privata.

Più efficacemente, la placchetta dell’uomo nudo incatenato su pira ardente, di cui alla Figura 1, potrebbe essere messa in relazione con un’altra placchetta di attribuzione e significato altrettanto complessi [Figura 4].

Figura 4. Allegoria della Fedeltà, bronzo, diametro cm. 5,6 circa, Italia settentrionale, 1500 circa, collezione Max Falk n. RA8 (ivi attribuita al Maestro IO.F.F. e datata al 1468-1474).

Per quanto riguarda la descrizione e interpretazione faccio riferimento a una fonte autorevole: il catalogo delle collezioni dell’Ashmolean Museum di Oxford, terzo volume, dedicato alle sculture medioevali e rinascimentali, curato da Jeremy Warren e pubblicato nel 2014.

Nella sezione che include le placchette, al numero 394, la placchetta viene definita Allegoria della Fedeltà e così descritta: un uomo nudo al centro aggredito da tre leoni (nota 7), sullo sfondo una sfera celeste (sfera armillare) con un cartiglio su cui si legge AM/ANDO/IO, lungo il bordo la scritta ET. SI. CORPVS. NON. FIDES/MACVLABITVR (se il corpo viene macchiato, non così la fede). Warren ci informa che esistono altri esemplari privi della sfera armillare in cui compaiono, alternativamente, altre scritte come ANCI MORTE.CHE RONPERE FEDE oppure ANCI/MORIR CHE/ RONP/ERE/FEDE (la morte piuttosto di tradire la fede) (nota 8) che, tuttavia non modificano il senso di sottoporsi a un sacrificio pur di salvaguardare la propria fede (cristiana).

In quest’ottica, i tre leoni potrebbero evocare proprio il martirio subito dai primi cristiani fatti divorare dai leoni al circo. Siamo in presenza di un messaggio religioso cristiano, veicolato attraverso un’immagine di tipo pagano (nota 9).

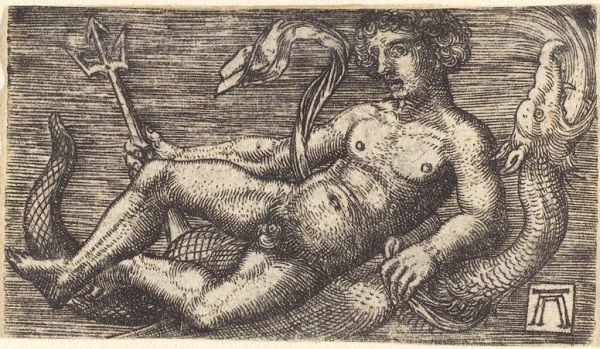

Sul fronte attributivo, Warren conclude che non vi sono elementi sufficienti per assegnare la placchetta al Maestro IO.FF e propende quindi per un ignoto fonditore dell’Italia settentrionale, ma prima cita alcune immagini di riferimento: un’incisione di Nicoletto da Modena raffigurante Lazzaro (“Lazarus”), che non è stato possibile identificare, il verso di una medaglia di Maometto II di ignoto medaglista [Figura 5] e un’incisione di Albrecht Altdorfer raffigurante Nettuno [Figura 6].

Figura 5. Medaglia di Maometto II, bronzo, diametro cm. 6,0, metà circa del XV secolo, Vienna, Kunsthistoriche Museum, Gabinetto numismatico, inv. 19032bß.

Figura 6. Albrecht Altdorfer, Nettuno, incisione.

Potremmo usare gli stessi riferimenti per la placchetta raffigurante Uomo nudo incatenato su pira ardente della Figura 1 di cui vorrei riprendere l’analisi, alla luce di quanto emerso a proposito della placchetta di Figura 4.

Anche in questo caso, ci troviamo di fronte un soggetto pagano che richiama i bassorilievi di epoca romana e saremmo tentati di classificare la nostra placchetta come un’Allegoria dell’Amore, combinando le metafore dell’amore che incatena e dell’amore che arde.

Tuttavia, percorrendo la strada di un’interpretazione in senso religioso, potremmo assegnare alla placchetta un significato di tipo moralistico.

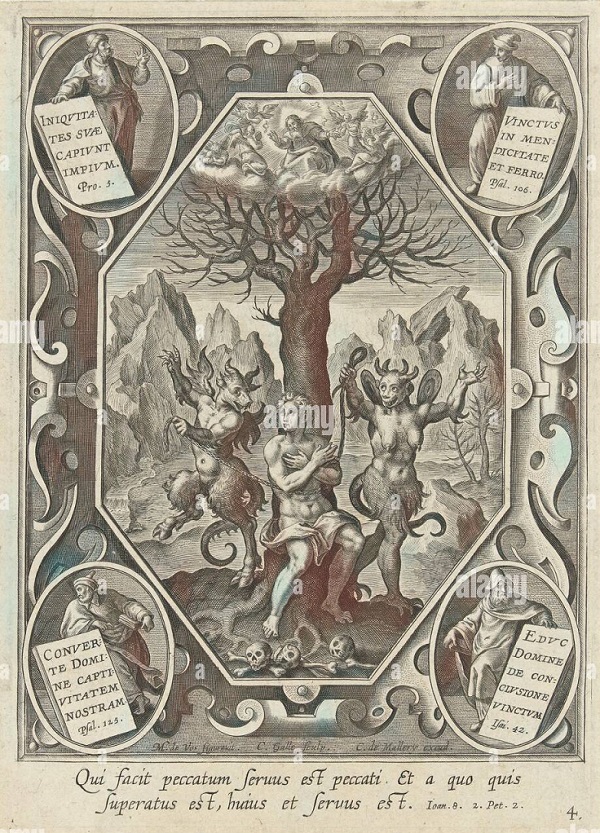

Per spiegarmi meglio, mostro un’incisione reperita abbastanza casualmente durante la ricerca di immagini di uomini nudi incatenati: un’illustrazione delle Meditazioni divotissime sopra l’amore di Dio di Diego Stella, libro pubblicato nel 1740 a Padova nella stamperia del Seminario presso Giovanni Manfre (nota 10).

Si tratta di una delle numerose edizioni italiane di quello che viene considerato uno dei capolavori della mistica del Cinquecento, ossia Cien meditaciones devotissimas del amor de Dios, scritto nel 1576 dal padre francescano spagnolo Diego de Estella (1524-1578).

Nell’incisione [Figura 7] si vede un uomo semi nudo, legato a un albero da due demoni in un paesaggio desolato.

Figura 7. M. de Vos-C. Galle-C. de Mallery, incisione, tratta da Meditazioni divotissime sopra l’amore di Dio di Diego Stella, Padova 1740 (fonte Alamy).

La combinazione dell’immagine con le scritte (nota 11) ci induce a interpretare la placchetta di Figura 1 come un’Allegoria del riscatto dal peccato; quindi, non elogio del martirio come nel caso della placchetta di Figura 4 (nota 12) e nemmeno un’allegoria dell’amore crudele.

Sia nella placchetta, sia nell’incisione, l’uomo appare nudo e indifeso, imprigionato in un contesto infernale, evocato nella prima dalle fiamme, nella seconda dai demoni.

Non sappiamo cosa indichino, nella placchetta, le cifre I.T.F., ma potrebbero essere un corrispettivo sintetico di alcune invocazioni che compaiono nella placchetta come “Signore libera dalla costrizione chi è incatenato”. In questo caso, la definizione fornita nel catalogo di Spink di Figura allegorica di uno schiavo, se intesa come “schiavo del peccato”, potrebbe essere stata azzeccata (nota 13).

NOTE

[1] Bronzo, diametro cm. 3,2. Identificativi: numero catalogo generale 02137535; Inventario corrente Bronzi, 1877, numero Bronzi 0520; inv. Municipio n. 68; Gabinetto Numismatico e Medagliere, inv. 266.

[2] Fetonte, figlio di Apollo, alla guida del carro del sole si era avvicinato troppo alla terra facendo numerosi danni e per questo Zeus lo punisce facendolo precipitare.

[3]

Der Cicerone.Halbmonatsschrift für die Interessen des Kunstforschers & Sammlers (Il Cicerone. Pubblicazione semestrale per gli interessi di ricercatori e collezionisti d’arte) è una rivista pubblicata tra il 1909 e il 1930 a Lipsia dall’editore Klinkhardt & Biermann.

La placchetta che, nel pomolo di spada, fa da controparte a quella dell’uomo nudo su pira ardente è altrettanto rara e meriterebbe una trattazione a parte. Al suo proposito, nel testo di Habich si legge: “Die andere Seite, Personifikation des Sieges in Gestalt eines geflügelten Genius mit eine kleinen Viktoria in der Linken, dem zwei nackte Krieger hildingen nahen, wird dem Antico zugenschrieben” (L’altro lato, personificazione della Vittoria nelle sembianze di un Genio alato con una piccola Vittoria nella mano sinistra, a cui si avvicinano in omaggio due guerrieri nudi, è attribuito all’Antico [Pier Giacomo Alari Bonacolsi detto l’Antico, 1460 circa-1528]).

[4] Si tratta di Die Italianischen Bronzen der Renaissance und der Barock, zweiter teil (seconda parte), Reliefs un Plaketten. Staaliche, catalogo del Museo di Berlino redatto da Ernst Friedrich Bange e pubblicato a Berlino da Walter De Gruyter nel 1922. Bange descrive brevemente la placchetta (di cui fornisce il diametro: cm. 3,5) e cita sia il Molinier, sia l’articolo di Habich pubblicato sulla rivista Cicerone del 1910 di cui sopra.

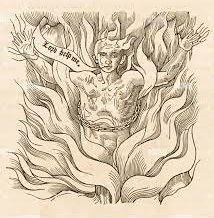

[5] A titolo di mera curiosità, segnaliamo che I.T.F. è universalmente noto come l’acronimo di Into The Fire. Inutile dire che questa decrittazione è del tutto irrilevante, così come fuorviante ai nostri fini è l’immagine di un uomo incatenato tra le fiamme (sicuramente un uomo messo al rogo) dove, su un cartiglio, si legge Lord save me [Figura A].

Figura A. Burnig at stake, illustrazione non identificata (fonte Alamy).

[6] Su questa placchetta e sull’ipotesi che alcuni esemplari possano essere di fattura moderna, si rimanda all’articolo A proposito di un gruppo di paci derivanti dalla Pietà del Moderno (aprile 2018) [ Leggi ].

[7] In un contesto totalmente diverso, troviamo i tre leoni “aggressivi”, questa volta a spese di un cavaliere, in una placchetta di Giovanni Francesco Enzola (Molinier 1886, I, n. 97) [Figura B].

Figura B. Giovanni Francesco Enzola, Cavaliere contro tre leoni, bronzo, fine XV secolo (fonte wikimedia).

[8] L’esemplare che si conserva presso la National Gallery of Art di Washington (fig. 347) ha un verso su cui compare un fregio con nereidi e tritoni con al centro un monogramma composto dalle lettere MARC di difficile interpretazione.

[9] Sulla possibilità di interpretare in modo originale il significato di una placchetta allegorica, si rimanda all’articolo Allegoria di Fama e Giustizia del Riccio, una nuova interpretazione (luglio 2023) [ Leggi ].

[10] Autori dell’incisione sono Marteen de Vos (1532-1603), che si qualifica come inventore (figuravit), Cornelis Galle (1576-1650) come incisore (sculpsit) e Carlo de (Karel van) Mallery (1571-1635) come stampatore (excudit).

[11]

Alla base si legge Qui facit peccatus feruus est peccati. Et a quo quis superatus est, huius et feruus est (Ioan 8. 2.Pet. 2.) ossia “Chi commette peccato è schiavo del peccato. E chi adesso ha ceduto, ne è schiavo anch’egli”.

All’interno dei medaglioni, partendo da quello in altro a sinistra e procedendo in senso orario, si legge: Iniquitates suae capiunt impium (Pro. 5) (L’empio è preda della sua iniquità); Vinctus in mendicitate et ferro (Sal. 106) (Prigioniero della miseria e delle catene); Educ domine de conclusione vinctum (Isai. 42) (Signore libera dalla costrizione chi è incatenato); Converte domine captivitatem nostram (Sal. 125) (Toglici o Signore dalla nostra prigionia).

Per quanto riguarda le fonti delle Sacre Scritture da cui sono tratte le frasi, Ioan 8 si riferisce al capitolo 8 del Vangelo di Giovanni; 2.Pet. 2. al capitolo 2 della seconda lettera di Pietro; Pro. 5 al capitolo 5 del Libro del Proverbi; Sal. 106 al salmo 106 del Libro dei Salmi; Isai 42 al capitolo 42 del Libro di Isaia; Sal. 125 al salmo 125 del Libro dei Salmi.

[12] È forse persino superfluo precisare che la placchetta di Figura 1 non rappresenta il martirio di San Lorenzo che era posto su una graticola e non era incatenato.

[13] Segnaliamo per completezza una placchetta pubblicata da John Pope Hennessy nel catalogo della Collezione Kress edito nel 1965 con il titolo di Giovane nudo (Naked Youth), attribuita a ignoto artefice italiano della prima metà del Cinquecento dopo aver contestato una precedente attribuzione al Moderno [Figura C].

Figura C. Giovane nudo, bronzo, Italia, prima metà del XVI secolo (J. Pope Hennessy Pope-Hannessy, Renaissance bronzes from the Samule H. Kress Collections. Relief, plaquettes, utensils and mortars, Phaidon. Londra 1965, p. 111 n. 411 fig. 395.

Anche questa placchetta risulta molto rara ma, a parte il fatto che raffigura un uomo nudo, la diversa postura e l’assenza di elementi distintivi di contorno (catene, fuoco, belve, ecc.) non consentono di collegarla al discorso svolto sopra.

Ringrazio Mike Riddick per lo scambio di idee ed Eugenia Fantone per la consulenza nelle traduzioni dal tedesco e dal latino.

Novembre 2023

© Riproduzione riservata

Post-scriptum (22.12.2023)

Grazie alla segnalazione di Mike Riddick, che ringrazio ancora sentitamente, è stato possibile accertare che l’esemplare della placchetta riprodotto in Figura 1 non è quello dei Musei di Berlino bensì del Cleveland Museum of Art.

Interpretation of a bronze plaquette depicting a naked man chained on a burning pyre

by Attilio Troncavini

I would like to deal here with a bronze plaquette that is as rare as it is unusual.

In his famous Les bronzes de la Renaissance. Les plaquettes, catalog raisonné, published in Paris in 1886, Emile Molinier classifies it as an anonymous work from northern Italy from the end of the 15th century and reports its presence in the Berlin Museum.

He describes it as follows: “752. Un Homme sur un bucher. Nu, de face, et le genou gauche appuyé sur la terre, la tete tournée vers la gauche, est enchainé par les poignets et les chevilles sur un bucher inflame. On the right, a benderole plusieurs fois replièe sur laquelle on lit: I.T.F.” (752. A man on a pyre. Naked, facing, his left knee resting on the ground, his head turned to the left, he is chained by the wrists and ankles on a burning pyre. On the right, a scroll folded several times on the which is read I.T.F.).

Below we show a archive image that could depict the specimen preserved in Berlin [Figure 1].

Figure 1. Naked man chained on a burning pyre, bronze, diameter cm. 3.2 approximately, Northern Italy, late 15th century, Berlin Museums (?) (Alamy source).

Another example is reported in Milan in the deposits of the Art Collections of the Castello Sforzesco (note 1).

The relevant sheet of the Regional Information System of Cultural Heritage (SIRBeC) is entitled Fall of Phaeton and thus identifies the subject within it, but in the description it refers, albeit doubtfully, to Prometheus.

The connection to Phaeton appears completely unjustified (note 2), but the one to Prometheus is also irrelevant. He steals fire from the Gods to give it to men and for this reason Zeus chains him to a cliff, but in his iconography an eagle always appears charged with ripping open his chest and tearing apart his liver.

We obtain some important information on the plaquette in question from the caption of the catalog of an auction held at Spink in London on 24 January 2008 in which a bronze example with a diameter of cm 3.2 was presented (lot 52), as an Italian school of the 15th century and with the title Allegorical figure of a Captive.

In the same caption, the writing on the scroll is reported as I.T.F. or *T.F because, evidently, the first letter is not entirely distinguishable.

We also read that, in the catalog of the Berlin Museum, the plaquette was attributed to the Moderno and that it was the only published example, that the letters could be the signature of the maker and that a similar plaque forms the pommel of a sword which found in Munich in the State Numismatic Collection.

In this last regard, the following publication is cited: Georg Habich, Schwertknaufe der Renaissance, in Cicero 1910 (note 3), which allowed us to trace the image of the sword pommel [Figure 2].

Figure 2. Sword pommel, Munich, Staatiche Munzsammlung (Der Cicerone 1910, plate extra text).

As regards the reference bibliography, the caption of the Spink catalog reports Molinier n. 752 (see above) and Bange n. 440 (note 4).

The hypothesis that behind the acronym I.T.F. the author of the plaquette is hidden, so it seems premature to think of the existence of an ITF Master (note 5).

As regards the attribution to the Moderno, we can only mention, without signing any conclusions, the plaquette depicting a Deposition, of which numerous examples are known in as many variations, whose arrangement of Christ’s arms and legs can recall that of our man [Figure 3, note 6].

Figure 3. Moderno, Deposition, bronze, private collection.

More effectively, the plaquette of the naked man chained on a burning pyre, shown in Figure 1, could be related to another plaque of equally complex attribution and meaning [Figure 4].

Figure 4. Allegory of Fidelity, bronze, diameter cm. 5.6 approximately, Northern Italy, around 1500, Max Falk collection no. RA8 (there attributed to Maestro IO.F.F. and dated to 1468-1474).

As regards the description and interpretation, I refer to an authoritative source: the catalog of the collections of the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford, third volume, dedicated to medieval and Renaissance sculptures, edited by Jeremy Warren and published in 2014.

In the section that includes the plaquettes, at number 394, the plaquette is defined as an Allegory of Fidelity and described as follows: a naked man in the center attacked by three lions (note 7), in the background a celestial sphere (armillary sphere) with a scroll on which it reads AM/ANDO/IO, along the edge the writing ET. YES. CORPVS. NOT. FIDES/MACVLABITVR (if the body is stained, not so the faith). Warren informs us that there are other specimens without the armillary sphere in which appear, alternatively, other writings such as ANCI MORTE.CHE RONPERE FEDE or ANCI/MORIR CHE/ RONP/ERE/FEDE (death rather than betraying the faith) (note 8) which, however, do not change the meaning of undergoing a sacrifice in order to safeguard one’s (Christian) faith.

From this perspective, the three lions could evoke the martyrdom suffered by the first Christians who were devoured by lions at the circus. We are in the presence of a Christian religious message, conveyed through a pagan image (note 9).

On the attribution front, Warren concludes that there are insufficient elements to assign the plaquette to Master IO.FF and therefore leans towards an unknown foundryman from northern Italy, but first cites some reference images: an engraving by Nicoletto da Modena depicting Lazarus (“Lazarus”), which I was unable to identify, the reverse of a medal of Muhammad II by an unknown medalist [Figure 5] and an engraving by Albrecht Altdorfer depicting Neptune [Figure 6].

Figure 5. Mohammed II medal, bronze, diameter cm. 6.0, approximately mid-15th century, Vienna, Kunsthistoriche Museum, Numismatic Cabinet, inv. 19032bß.

Figure 6. Albrecht Altdorfer, Neptune, engraving.

We could use the same references for the plaquette depicting a naked man chained on a burning pyre in Figure 1, which I would like to resume the analysis of, in light of what emerged regarding the plaque in Figure 4.

Also in this case, we are faced with a pagan subject that recalls the bas-reliefs of the Roman era and we would be tempted to classify our plaque as an Allegory of Love, combining the metaphors of love that chains and love that burns.

However, following the path of an interpretation in a religious sense, we could assign a moralistic meaning to the plaque.

To explain myself better, I show an engraving found quite randomly during the search for images of naked men in chains: an illustration of the Meditations devotissime sopra l’amore di Dio by Diego Stella, a book published in 1740 in Padua in the Seminary printing press of Giovanni Manfre (note 10).

It is one of the numerous Italian editions of what is considered one of the masterpieces of sixteenth-century mysticism, namely Cien meditaciones devotissimas del amor de Dios, written in 1576 by the Spanish Franciscan father Diego de Estella (1524-1578).

In the engraving [Figure 7] we see a semi-naked man, tied to a tree by two demons in a desolate landscape.

Figure 7. M. de Vos-C. Galle-C. de Mallery, engraving, taken from Meditations devotissime sopra l’amore di Dio by Diego Stella, Padua 1740 (Alamy source).

The combination of the image with the writings (note 11) leads us to interpret the plaquette in Figure 1 as an Allegory of redemption from sin; therefore, not a praise of martyrdom as in the case of the plate in Figure 4 (note 12) nor an allegory of cruel love.

Both in the plaquette and in the engraving, the man appears naked and defenseless, imprisoned in an infernal context, evoked in the first by flames, in the second by demons.

We do not know what the I.T.F. numbers indicate on the plaquette, but they could be a synthetic equivalent of some invocations that appear on the plaquette such as “Lord free from constraint those who are chained”. In this case, the definition given in Spink’s catalog of Allegorical figure of a slave, if understood as “slave of sin”, may have been apt (note 13).

NOTE

[1] Bronze, diameter cm. 3.2. Identifiers: general catalog number 02137535; Current inventory Bronzes, 1877, Bronze number 0520; inv. Municipality no. 68; Numismatic and Medal Cabinet, inv. 266.

[2] Phaeton, son of Apollo, driving the chariot of the sun had come too close to the earth causing numerous damages and for this Zeus punished him by making him fall.

[3]

Der Cicerone.Halbmonatsschrift für die Interessen des Kunstforschers & Sammlers (The Cicerone. Semi-annual publication for the interests of art researchers and collectors) is a magazine published between 1909 and 1930 in Leipzig by the publisher Klinkhardt & Biermann.

The plaquette which, on the pommel of the sword, acts as a counterpart to that of the naked man on a burning pyre is equally rare and deserves a separate discussion. In this regard, in Habich’s text we read: “Die andere Seite, Personifikation des Sieges in Gestalt eines geflügelten Genius mit eine kleinen Viktoria in der Linken, dem zwei nackte Krieger hildingen nahen, wird dem Antico zugenschrieben” (The other side, personification of Victory in the guise of a winged Genius with a small Victory in his left hand, to which two naked warriors approach in homage, is attributed to the Ancient [Pier Giacomo Alari Bonacolsi known as the Ancient, circa 1460-1528]).

[4] This is Die Italianischen Bronzen der Renaissance und der Barock zweiter teil (part II), Reliefs un Plaketten, catalog of the Berlin Staaliche Museum, edited by Ernst Friedrich Bange and published in Berlin by Walter De Gruyter in 1922. Bange briefly describes the plaquette (of which he provides the diameter: 3.5 cm) and cites both Molinier and article by Habich published in the Cicerone magazine of 1910 mentioned above.

[5] By way of mere curiosity, we would like to point out that I.T.F. is universally known as the acronym for Into The Fire. It goes without saying that this decryption is completely irrelevant, just as misleading for our purposes is the image of a man chained in the flames (certainly a man burned at the stake) where, on a scroll, we read Lord save me [Figure A].

Figura A. Burnig at stake, illustrazione non identificata (fonte Alamy).

[6]On this plaquette and on the hypothesis that some examples may be of modern manufacture, please refer to the article About a group of peaces deriving from the Pietà del Moderno (April 2018) [ read].

[7] In a totally different context, we find the three “aggressive” lions, this time at the expense of a knight, in a plaquette by Giovanni Francesco Enzola (Molinier 1886, I, n. 97) [Figure B].

Figure B. Giovanni Francesco Enzola, Knight against three lions, bronze, late 15th century (wikimedia source).

[8] The example preserved in the National Gallery of Art in Washington (fig. 347) has a reverse on which appears a frieze with nereids and tritons with a monogram in the center composed of the letters MARC which is difficult to interpret.

[9] On the possibility of interpreting the meaning of an allegorical plaquette in an original way, please refer to the article Allegory of Fame and Justice by Riccio, a new interpretation (July 2023) [read].

[10] The authors of the engraving are Marteen de Vos (1532-1603), who qualifies as an inventor (figuravit), Cornelis Galle (1576-1650) as an engraver (sculpsit) and Carlo de (Karel van) Mallery (1571-1635) as a printer (excudit).

[11]

At the basewe read Qui facit peccatus feruus est sins. Et a quo quis superatus est, huius et feruus est (Ioan 8. 2. Pet. 2.) i.e. “Whoever commits sin is a slave to sin. And whoever has now given in is also a slave to it.”

Inside the medallions, starting from the one on the top left and proceeding clockwise, we read: Iniquitates suae capiunt impium (Pro. 5) (The wicked is prey to his iniquity); Vinctus in mendicitate et ferro (Ps. 106) (Prisoner of poverty and chains); Educ domine de conclusion vinctum (Isai. 42) (Lord frees from constraint those who are chained); Converte domine captivitatem nostram (Ps. 125) (Remove us, O Lord, from our captivity).

As for the sources of the Holy Scriptures from which the sentences are taken, Ioan 8 refers to chapter 8 of the Gospel of John; 2.Pet. 2. in chapter 2 of the second letter of Peter; Pro. 5 to chapter 5 of the Book of Proverbs; Sal. 106 to psalm 106 of the Book of Psalms; Isaiah 42 to chapter 42 of the Book of Isaiah; Sal. 125 to Psalm 125 of the Book of Psalms.

[12] It is perhaps even superfluous to point out that the plaquette in Figure 1 does not represent the martyrdom of San Lorenzo who was placed on a gridiron and was not chained.

[13] For the sake of completeness, we would like to point out a plaquette published by John Pope Hennessy in the catalog of the Kress Collection printed in 1965 with the title of Young Nude (Naked Youth), attributed to an unknown Italian artist from the first half of the sixteenth century after having contested a previous attribution to the Modern [Figure C].

Figure C. Nude youth, bronze, Italy, first half of the 16th century (J. Pope Hennessy Pope-Hannessy, Renaissance bronzes from the Samule H. Kress Collections. Relief, plaquettes, utensils and mortars, Phaidon. London 1965, p. 111 no. 411 fig. 395.

This plaquette is also very rare but, apart from the fact that it depicts a naked man, the different posture and the absence of distinctive surrounding elements (chains, fire, beasts, etc.) do not allow it to be connected to the discussion above.

I thank Mike Riddick for the exchange of ideas and Eugenia Fantone for consultancy in translations from German and Latin.

Post-scriptum (22.12.2023)

Thanks to the reporting by Mike Riddick, whom I sincerely thank again, it was possible to ascertain that the example of the plaquette reproduced in Figure 1 is not that of the Berlin Museums but of the Cleveland Museum of Art.